Deciphering Our Statistics

Official categories for deaths in custody under the Deaths in Custody Reporting Act are: Cancer, Heart disease, Liver disease, Respiratory disease, AIDS-related, All other, Suicide, Drug/alcohol intoxication, Accident, Homicide, Other/unknown, and Missing. Framing refers to process by which communicators “select” certain elements to focus on while excluding others in order to transmit certain normative judgments.[1] Yet these categories fail to acknowledge the role of the Department of Corrections.

The state repeatedly claims over and over again that it has no fault in the deaths that occur within the walls of its institutions, but the pattern of neglect persists.

The death dealing practices of the state both function through killing–the “smart bomb”, the police officer shooting an unarmed youth–but also by letting people die. The Illinois Department of Corrections has allowed too many people too die and hid the true circumstances of their death behind broad categories and statistical abstraction.

We break down each of these categories and offer some context:

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), Illinois’ prisons have a suicide rate of 16 per 100,000 “inmates”, almost double the suicide rate for the general public.[2] Nationally, “suicide was the leading cause of death in jails every year since 2000,” according to the BJS, Incarceration creates and exacerbates mental health crises and the system is more than woefully unprepared: it is complicit.

Though the state of Illinois has faced numerous lawsuits over its insouciant handling of mental health for people in prison, little has changed. Illinois ranks 49th in the United States in terms of its per-inmate health care spending. In 2005, Hassiba Belbachir, an Algerian native who loved dancing the merengue, religion, and wanted to visit the world, according to family members, was incarcerated at the McHenry County Jail after seeking asylum. After a suicide attempt, the jail staff did little to address Belbachir’s needs and she was found dead eight days after being locked up. The outrage surrounding her death and litigation highlighted the gross negligence of corrections staff. The case was settled in 2014 with the state contractor responsible for providing health care services to the McHenry County Jail, Centegra Health Systems, admitting no fault. As of 2014, Centegra Health Systems still provides health services, according to the jails PREA audit. The same negligence appeared in the 2004 death of May Molina, an anti-police activist the Chicago Tribune described as, “a thorn in the side of the Chicago police for years.” The medical examiner ruled her death “accidental,” even though Molina, who suffered from diabetes and thyroid ailments, did not receive any of her medications while incarcerated. A federal jury found the state at fault and awarded Molina’s family $1 million.

Molina and Belbachir reveal how state officials mask their responsibility for deaths in custody behind the veneer of official statements and neat causal explanations. The lack of oversight outside of civil litigation limits the options of families, particularly for those who lack the economic capital or jurist interest necessary to wage a lengthy legal battle against the state. In both cases, the lawsuits dragged on over nearly a decade exacting an economic and emotional toll. This system allows officials to get away with murder.

As admitting negligence would implicate the state, the official story concocts statistical falsehoods, with the knowledge that only litigation—costly, draining, and out-of-reach for many—can secure transparency.

The poor health outcomes of people under IDOC control have received some scrutiny. A 2015 Illinois Department of Corrections appointed panel reviewed 63 inmate deaths and concluded that in 60% of the deaths there was a “significant lapse in care.” Among the other findings in the 405-page document: a systemic failure to treat even ordinary illnesses like diabetes. Yet the report’s critical tone led the IDOC to dispute the findings.

Mental health care in Illinois’ prisons and jails is similarly abysmal. Rasho v. Baldwin, a case filed in 2007, asserted that “Illinois punishes mental illness instead of treating it.” The case was settled in December 2015 and IDOC has agreed to:

- Hire 300 new mental health workers, as well as additional security and administrative staff

- Renovate spaces in three prisons to improve mental health care and and build one entirely new mental health facility/prison

- Create 50 desperately needed beds for people whose mental illness necessitates hospitalization

- Require individuals with mental illness who are in solitary confinement for longer than 60 days to spend at least 20 hours out-of-cell each week

Statistics obfuscate with clear cut, disciplinary categories. Even with institutional reporting, the recent legal history and state of health care in Illinois’ correctional facilities reveals a disturbing pattern of preventable death and staff attempts to cover those deaths up.

[1] Robert M. Entman. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” 43.3 (Autumn 1993). 51 – 58.

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2014 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2015. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2014, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html

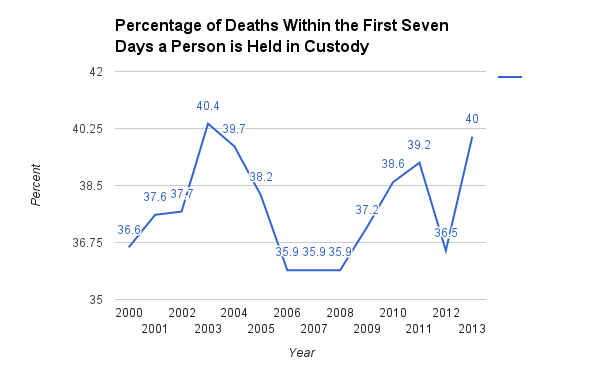

A Brief Note on Timing

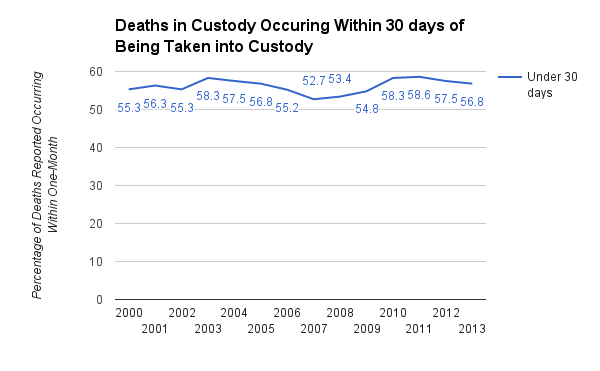

Over the last thirteen years, the plurality of institution reported deaths have occurred within the first seven days a person is held in custody. The state of Illinois appears to hew closely to this trend as three (Dutkiewicz, Clifton, and Butterfield) of the eight deaths in 2016, thus far, have occurred within seven days. The majority of deaths reported by institutions from 2000-2013 occur within one month of a person’s being taken into custody.

Five of the eight deaths we found during 2016 occurred within one month–Butterfield, Clifton, Cruz, Dutkiewicz, and Lynch . This alarming pattern points toward inadequate care for mental and physical health.

On Mourning

“They didn’t have the decency to call”

When 45-year-old Toya Frazier died in December 1 2015, officials at Champaign County Jail took no steps to inform her family. That evening one of Frazier’s friends, who was incarcerated at the jail, called Frazier’s sister to tell her that Toya died. It took officials nearly three weeks to send a letter to the family.

This official response reveals the limits of grief—who can be grieved and who has a right to grieve—and these rules differ depending on who has died and that person’s relationship to the state. When public figures die, even those who push hate-based and exclusionary policies, somber mourning and respect ensue. When those disappeared by the state into our nation’s jails and prisons die there is silence. Even private grief is an afterthought to officials, who delay notification and utilize official documents to inform the deceased’s loved ones of their passing.

The question of mourning is key to understand the politics of life and death that have always defined modern state. Judith Butler interrogates how our capacity to publicly mourn is “foreclosed by our failure to conceive of… lives as lives.”[1] Through her study of the “War on Terror”, Butler proposes grieving as a way of going beyond “narcissistic melancholia” by contemplating “the vulnerability of others.”[2]

Whose lives matter, and by extension can be grieved, is imprisoned in the US penitentiary system. Concrete walls and their paper equivalents figurally obscure the process of letting die that goes on every day in jails and prisons through a lethal cocktail of official neglect and public disinterest. The use of statistics and byzantine bureaucratic systems limits the grievability of those inside because we do not know of their deaths. When deaths are disclosed, public discourse focuses on “crime” and “punishment” portraying the individuals as unworthy of grief. The lack of public mourning for the tens of thousands of inmates who die every year embodies the tacit acceptance of official explanations and justifications.

Restoring public mourning and public grief for those who die while incarcerated is necessary to challenge the systems of public neglect that allow for the perpetuation of massive institutional violence.

[1] Butler, Judith. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso (2004). p. 12.

[2] Butler (2004). p. 30.

Outside Sources/Media

When jail is used as drug treatment: http://smilepolitely.com/culture/when_jail_is_used_as_drug_treatment/

WBEZ – $6.4 Million Recommended in 2 Police Custody Death Cases: https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-news/64-million-recommended-in-2-police-custody-death-cases/ffd61364-ac31-402f-9817-a6ee05a11d18

How Privatization Destroyed an Illinois Jail’s Award-winning Suicide Prevention Program: https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2013/sep/15/how-privatization-destroyed-an-illinois-jails-award-winning-suicide-prevention-program/